Letter to The New York Times, 2 June 2015, containing admissions so rare that it deserves to be treated like a sacred tooth of the Buddha (Scroll down to see the words missing from the edge of the print

text clipped in haste)

…

Two years have gone by since the last entry on this site and almost three since the release at the end of April, 2019 of the California Auditor’s report on precisely how the body charged with disciplining badly behaved, unethical and incompetent judges has been failing California taxpayers — an unforgettable set of documents crammed with unnerving details. Since then, exactly as expected, the San Francisco-based Commission on Judicial Performance has given anyone paying attention a master-class in evasion and foot-dragging, its fallback options after its attempt to block the audit by suing the Auditor delayed its commencement for two years but failed to cripple it. That lunge at fending off scrutiny should make it obvious that the pandemic cannot be blamed for the CJP’s failure to follow the report’s recommendations of a revolutionary overhaul of its methods and structure.

The worst news for anyone who cares about justice in the state whose technology pioneers — not restricted to Apple, Facebook, and Google — are transforming human life is that California’s fearless and indefatigable Auditor, Elaine Howle, announced her resignation in October. The few websites that gave this development the high profile it deserved did not remark on the oddness of a 63 year-old official whose work had won nothing but praise in her twenty-one years in the position choosing not to wait for just two more to reach retirement age.

The reasons she gave for her departure were superficially unremarkable — ‘I think it’s time for the next generation of leaders to take over,’ and ‘It’s time to dial it back a little bit and enjoy life.’ As recently as 2019, however, she had said: ‘We look forward to reviewing evidence of how CJP implements our recommendations,’ adding that ‘[o]ur report describes significant gaps in CJP’s oversight of potential patterns of judicial misconduct.’ Though she had several other critical audits to direct after that — such as California’s management of the pandemic — she could only have been disappointed by what has happened subsequently.

In March of this year, the lower house of the California legislature passed a curious bill, AB-1577. In part, it reads as a bizarre restatement of the CJP’s charter with microscopic alterations — not unlike a medical standards enforcement board being reminded that it is supposed to prevent doctors from killing their patients. The rest of it is about setting up a fifteen-member committee headed by a judge and including a few non-expert Californians, a panel whose — incredible — remit is to look into whether the CJP actually needs to be reformed at all. Yes … that is in spite of the Auditor’s damning revelations about a modus operandi that only a lunatic could deem honest, diligent, or acceptable, and her report’s comprehensive, minutely specific outline of what needs changing.

Nine months have gone by since March, yet this bill has not yet been passed by the Senate and signed into law by the governor — though the committee yet to be formed is supposed to submit its conclusions by March of 2023.

A logical deduction for onlookers is that creeping progress first in authorising, then staffing, a panel to tread the ground that California’s specialist in exposing poor or deficient government has already covered is simply the CJP’s failed lawsuit in another form — that is, a new ruse for delay and obstruction, if not outright derailment.

It is probably a foregone conclusion that the CJP has won its most crucial argument with the Auditor, which was about the need to restructure the CJP so that the same group of people whose job is deciding whether particular judges accused of misconduct by members of the public are guilty is not also investigating the charges against them. As noted earlier on this site, there is nothing in such a set-up to prevent those people from finding no evidence whatsoever to justify complaints. The positions of the Auditor and the CJP in this dispute are easily discerned in this statement by Elaine Howle’s office after her report was published:

‘[W]e state that although it is not identical in nature, CJP’s structure is analogous to a jury in a criminal case being composed of detectives who investigated that case. CJP believes that this analogy is unfortunate and wrong. We disagree. Much like detectives who investigate allegations of criminal activity, commissioners are privy to allegations of misconduct that are not ultimately proven by evidence … In the criminal justice system, the roles of the investigator—a detective—and the ultimate decider—usually a jury—are purposefully separated to ensure that individuals receive impartial trials. ‘ [ Highlighting is by COTIN ]

Aside from AB-1577, the other reason for pessimism about significant procedural or organisational alterations at the judges’ disciplinary agency is in the reaction of the CJP’s leader, Gregory Dresser, to the formation of the superfluous must-it-really-change? panel — on which he is expected to sit:

‘“If the Legislature passes the bill and the governor signs it into law, I look forward to working with the committee … to discuss and study possible improvements to the operations of the commission,” said Gregory Dresser, the commission’s director and counsel in chief.’ [ Highlighting of this extract from The Recorder, 13 April 2021, is by COTIN ]

…

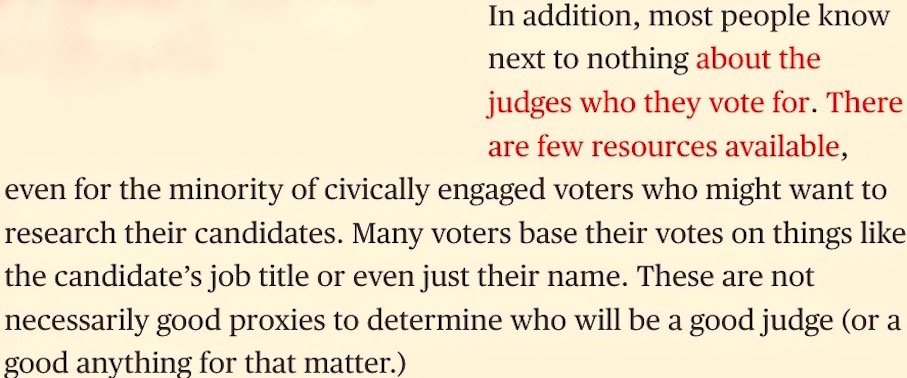

Yes, there are still good — even exemplary — judges, a point underlined in this space before. Yet a scrap from a newspaper preserved in a 2015 diary and forgotten until it fell out of its pages, recently, is proof from the upper reaches of the U.S. judiciary that not all those who sit on its benches deserve the high esteem in which they are held by — typically — too-trusting members of the public. Visitors browsing The Robing Room website, where the men and women in black robes are reviewed by both advocates and litigants, can read their depressing testimony about their experiences. The worst judges are every bit as guilty of protecting their selfish collective interest as lawyers colluding in their code of silence.

The six year-old newspaper clipping, pasted in below** — a former federal judge’s letter to The New York Times — is a rare acknowledgment by an insider that conspiracies of silence are not merely at odds with the public interest but do actual harm.

His independence of mind deserves highest praise. Where are the others like him?

…

June 2, 2015

To the Editor:

Re “Stumped, Your Honor? Call a Judge” (news article, May 20):

About a week after I became a judge on the Federal District Court, a request was made to seal the record in a case in connection with a proposed settlement. I conferred with an experienced colleague, and he said that if all the lawyers and litigants agreed, there was no reason not to sign it.

I did so, but immediately had misgivings about the propriety of a judge’s participating in the concealment of information that might be of interest to the public — for example, regarding defective or dangerous products.

From that moment on, I never sought advice from any of my colleagues. I decided that my mistakes should be my own, although I certainly do not criticize those who seek the wise counsel of their brethren.

H. LEE SAROKIN

La Jolla, Calif.

The writer is a retired judge of the United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit.