…

What if the performance of judges across the U.S. could be monitored by an equivalent of the National Basketball Association’s four year-old, high-tech, Replay Center — in which referees vet the fairness and accuracy of other referees in games played across the country, without delay?

This web site’s focus on using technology to make today’s too often strictly nominal courts of justice radically transparent — and so, fully accountable to citizens — is in perfect sync with Against the Rules, a podcast by Michael Lewis, who is best-known as the author of Moneyball and The Big Short.

Launching his series in late April, he explained to The New York Times that his subject was ‘all the poorly refereed corners of life’ — and growing, mass outrage about the reflexive tendency of ‘[t]he privileged to try to protect what they have by evading authority and regulation.’

In the podcast’s introductory segment, one of Lewis’s interviewees tells him that ‘whether it’s in baseball or any other walk of life, you cannot turn the clock back on transparency.’

Nor is there going to be any more reflexive genuflecting before undeserved or unearned authority, in any profession or post — even if it is only this one class of sport referee, in American basketball, that has so far acquired such a comprehensive, systematised check on its latitude for biased, corrupt, or otherwise delinquent behaviour. As Lewis sums up his discoveries about its genesis and effects, ’Everyone believed that the only way to ensure the fairness of the game was to let the referee play God. The Replay Center is an admission that the referee is not God — and that he makes mistakes.’

It is an innovation that appears to have been a great success. Nothing could gladden the hearts of fighters for genuine impartiality and fairness more than the evidence of changes in the right direction that the Replay Center appears to have brought about.

What follows are extracts from the transcript of ‘Hoop Reams,’ an edition of National Public Radio’s This American Life that featured a special condensation of Against the Rules — after a framing narrative by Ira Glass, the show’s host.

Ira Glass: The journalist Michael Lewis, … was looking around at what’s going on in America these days. And he noticed that one way you can describe the current moment that we’re all living through is that Americans don’t trust the refs — in all walks of life. They don’t trust their impartiality.

I’m talking about police, Supreme Court justices, journalists, the people who regulate the banks and Wall Street and student loans, the people setting medical costs, judges. So many people today feel the system is rigged. I mean, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump both ran on that. So many people feel that the figures of authority, charged with enforcing rules impartially, keeping everybody on a level playing field, that they’re failing at their jobs.

[ … ]

Michael Lewis: … So we’re walking across a parking lot in Secaucus, New Jersey. And there are chain hotels and motels in someone’s idea of a mall. And we’re surrounded on all sides by freeways. … And we’re approaching a four-story, rectangular, otherwise nondescript concrete building.

There’s a discreet little sign here that says NBA and shows a logo with a basketball player. Inside, a recent concession to the world we live in– the Replay Center, a place where basketball referees review the calls made by other basketball referees in real time, to minimize referee error. The Replay Center was built to persuade people that life was fair.

… It’s wall-to-wall screens, 110 of them. What’s on them is whatever is captured by all the cameras in 29 NBA arenas across the country. They may have a screen somewhere with scores on it, but I didn’t see it. And they’re all muted. What you hear is referees staring at basketball games. What you see is nothing but angles on professional basketball courts.

… These Replay Center refs have video technicians with them, who can freeze a moment on screen, then zoom out or zoom in so that the entire screen contains only a player’s fingertips or his toes. Here you just scroll through tiny slivers of the game, not the game itself. The sliver is where injustices might occur.

[ … ]

Justin Wolfers: Look, I don’t really like writing papers about sports. I’d prefer to write about the economy.

Michael Lewis: That’s Justin Wolfers, a behavioral economist at the University of Michigan, and the co-author of a paper about NBA refs.

Justin Wolfers: But the thing is, this is a domain where the NBA referees have tremendous incentives not to make the wrong call. Every error they make is tracked. Those errors determine whether they get more games. Those games determine how much they get paid. This is arguably the most analyzed workforce in the country.

Michael Lewis: Basketball referees are now picked apart in ways that not long ago would have seemed preposterous– not just for the fairness of their calls but for their unconscious behavior. Wolfers took data from over a decade of NBA basketball games, more than 250,000 of them. Then he set out to look for evidence of the refs’ racial bias.

Justin Wolfers: The question here isn’t whether people are anti-black or anti-white but whether there’s an in-group bias. So if a predominately black team is playing and the refereeing crew is predominantly white, are there more fouls called against them than on nights when the same team is playing with a predominantly black refereeing crew? And it turns out, the answer is yes.

Michael Lewis: Wolfers wrote his paper back in 2007, before this new age of referee transparency. … And the NBA wasn’t happy. The commissioner at the time attacked the study and embarrassed the league by trying and failing to refute its findings. … When the dust settled, Justin Wolfers was curious to know if his paper had had any effect. He made another study of referees after the controversy he’d created. And guess what.

Justin Wolfers: The most recent study that we did seems to suggest that that form of racial bias has gone away.

Michael Lewis: For a while anyway. He has no idea why. Maybe simply making the refs aware of the problem was enough to correct it. By the way, the NBA disputes this study too. But in the end, this became a case study — not in ref ineptitude but in ref reform. NBA refs have now achieved what police forces can only dream of, though the refs have no choice. The world’s now too good at seeing their mistakes.

…

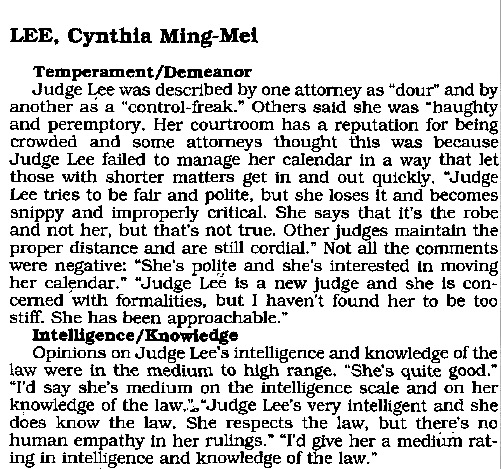

Regular readers of COTIN will remember last year’s post about the clear, incontrovertible evidence of racial bias in the rulings of American judges in the findings of Alma Cohen and Crystal Yang, for their study at the Harvard Law School — in the course of which they examined over 500,000 sentences handed down by nearly 1,400 federal judges between 1999 and 2015.

Imagine the difference that a Replay Center counterpart for judges could make to that pattern of injustice — for a start.