…

…

With or without human intervention — and for no discernible reason other than mentions of a Chinese-American judge with a Chinese-American name — the Google algorithm that indexes this site keeps drawing attention to a Chinese innovation that has largely been ignored by mainstream Western media.

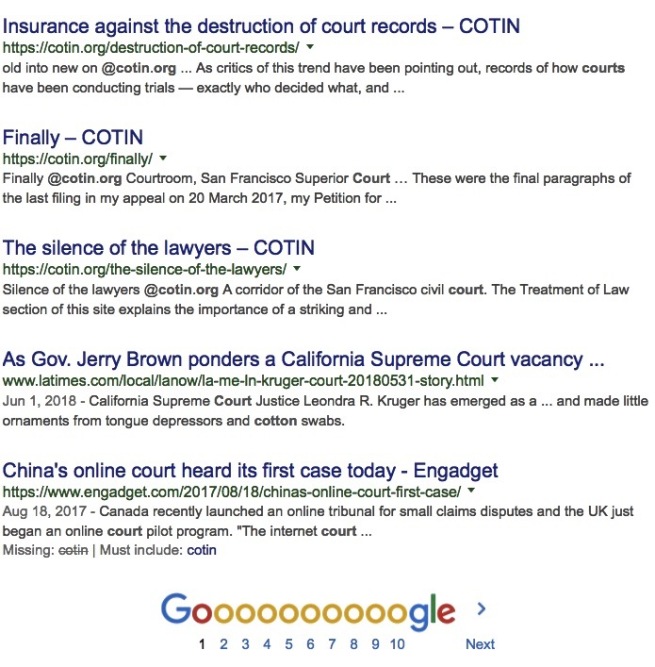

For several days, typing the terms ‘cotin.org courts’ into the search engine has yielded for a final result on page one — after nine results related to COTIN or California’s legal system, including one about Governor Jerry Brown and the Supreme Court — a link to a story on the Endgadget site dated 18 August 2017 and titled ‘China’s online court heard its first case today.’

Taken at face value, that news would mean that Britain has fallen behind China in putting its court system online — despite Lord Justice Briggs’s prediction in 2016, featured on another part of this site, that Britain would be first in moving a key element of court proceedings onto the internet, a ‘digitised “triage process”’. But when the China story surfaced last summer, Britain still only had what Endgadget called ‘an online court pilot program,’ while Canada, its closest rival, had launched ‘an online tribunal for small claims disputes.’ A German magazine reported that the Chinese had launched ‘probably the very first virtual court worldwide and will hear disputes arising from internet-related activities.’

But China’s legal system is sufficiently different from all its counterparts in the Western tradition to be incommensurable with them — lacking anything resembling a common yardstick.

Susan Finder, an American legal scholar who has spent more than thirty years of her career in Hong Kong and China, has explained that while ordinary Chinese people are beginning to understand that they have rights under law, ‘government officials at high and low levels don’t always have what the Chinese call “rule of law thinking”’. Speaking at a conference in California in 2016, she said that there is ‘a fuzzy line between law and party policy;’ that this policy changes often; and that government enforcement of law ‘presents practical issues’ for both individuals and companies.

It is a shame that those characteristics mean that there is probably not very much in the Chinese launch of a cyber or virtual court that Western legal systems can use as a guide or model.

If there were, the information would not necessarily be easy to come by. Professor Finder says that most writing on the Chinese legal system is ‘siloed,’ addressing specialists both inside and outside China. This is obvious from her web site that serves both as an English-language gateway to the online Supreme People’s Court and as a frame for ‘a blog discussing China’s highest court,’ of which she is an official ‘monitor’.

It is hardly her fault that this job, like much of her writing on the site, seems as mysterious, baffling and remote as might be expected from its deeply foreign context. About — for instance — the drafting of the first comprehensive overhaul of China’s ‘law of the people’s courts’ since 1979, she says: ‘Among the central Party authorities consulted were: Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, Central Organizational Department (in charge of cadres); Central Staffing Commission (in charge of headcount); Central Political Legal Committee.’

Yet in both China and Britain, the power of the internet is being harnessed for sweeping legal reforms with the same laudable, principal aim: transparency. As a 2016 BBC report from China noted about the commencement on tingshen.court.gov.cn of proceedings streamed online from (traditional rather than virtual) courts across the country:

According to Zhou Qiang, the head of China’s Supreme People’s Court, the streaming site will “better safeguard people’s right to know and supervise” but its value could go well beyond that, by helping Chinese citizens get a glimpse of what’s actually going on inside their country, beyond the filter of state-controlled media.